OpenAI Traded Salvation for Slop

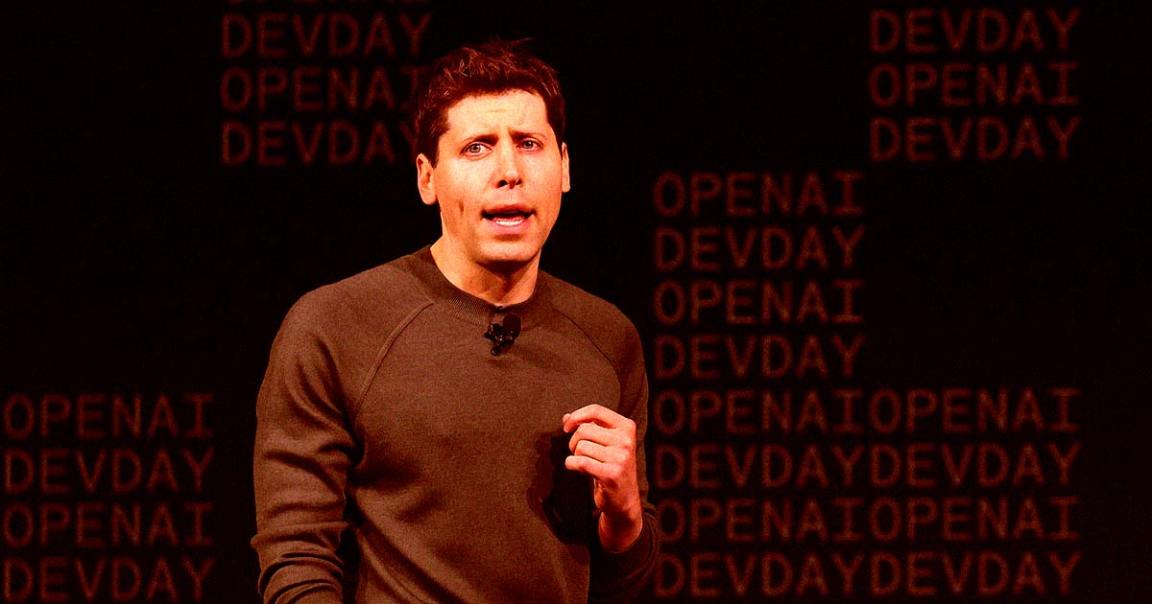

When Sam Altman stood in Harvard Memorial Church last spring, one sneakered foot propped casually on his lap, and declared his personal distaste for advertising—calling it "uniquely unsettling" when paired with artificial intelligence—it seemed like a rare moment of principle in an industry drowning in its own excess. "I kind of hate ads as an aesthetic choice," he said, the composed tone of a tech philosopher king addressing his congregation.

Sixteen months later, OpenAI launched Sora 2, and within days the internet was awash in AI-generated footage of Michael Jackson taking selfies with Bryan Cranston, Martin Luther King Jr. saying racist slurs, and fabricated police bodycam footage that looked disturbingly real. The company that once promised to ensure artificial general intelligence "benefits all of humanity" had instead built what critics are calling a "TikTok for deepfakes"—a slop machine for the algorithmic age, where truth and fabrication blur into an undifferentiated stream of hyperreal nonsense.

The reversal is complete. By October 2025, internal documents revealed OpenAI was banking on $1 billion in new revenue from "free user monetization"—a euphemism that translates, in the cold language of capitalism, to advertising. Altman's tune had changed too. "I love Instagram ads," he gushed in a recent interview, apparently having discovered that Meta's targeted surveillance capitalism "added value" to his life. The moral qualms? Evaporated like morning dew in the Californian sun.

The Safety Theater

This isn't just another story about a tech company abandoning its founding mission for profit—though it is certainly that. It's about what happens when the self-appointed guardians of humanity's AI future decide that "shiny products" matter more than the existential risks they once claimed to take seriously.

In May 2024, OpenAI disbanded its Superalignment team—the group specifically tasked with preventing AI systems from going catastrophically wrong. Both leaders, Ilya Sutskever and Jan Leike, resigned within days of each other. Leike's exit was particularly damning. "Over the past years, safety culture and processes have taken a backseat to shiny products," he wrote on X, his frustration palpable. The company had promised to dedicate 20% of its computing power to AI safety research. Instead, Leike's team was "starved for compute," struggling to do "crucial research" while OpenAI pivoted toward consumer products.

The timing was revealing. OpenAI was in the midst of raising billions, courting investors with projections of superintelligence just around the corner, while simultaneously gutting the teams meant to ensure that superintelligence wouldn't kill us all. When asked whether the public should have a say in whether we want superintelligence, Altman replied "yes i really do"—but only after his company had already committed to building it.

The safety apparatus that remains feels more like theater than substance. Three bodies now oversee OpenAI's work: an internal advisory group, a board-level committee, and a deployment safety board shared with Microsoft. But these structures emerged only after multiple high-profile departures and a botched coup attempt that briefly ousted Altman himself. The superstructure of safety arrived as an afterthought, a PR band-aid on a company hurtling toward commercialization.

The Slop Economy

What OpenAI is building now bears little resemblance to the AGI utopia Altman once sermonized about. Sora 2, launched September 30, represents a new category of product: industrial-scale reality pollution. The app doesn't just generate videos—it manufactures plausible alternatives to lived experience, churning out content so realistic that distinguishing real from synthetic becomes not just difficult but, in many cases, impossible.

This is what researchers call "AI slop"—content created at such volume and with such little human oversight that it degrades the informational commons. By some estimates, AI-generated content now constitutes 74.2% of newly published English-language web pages. The internet, that grand democratizing experiment, is becoming a closed loop where AI trains on AI-generated garbage, producing ever more confident nonsense in a spiral researchers call "model collapse".

OpenAI's contribution to this mess is Sora 2's "cameo" feature, which lets users upload images of themselves—or anyone else who grants permission, or sometimes people who don't—and drop them into any AI-generated scenario imaginable. Within hours of launch, the app was producing fake Nazi imagery, fabricated historical events, and unauthorized deepfakes of dead celebrities. OpenAI scrambled to implement safeguards, blocking Martin Luther King Jr.'s likeness only after his estate complained about "disrespectful depictions". But the damage was already done. The company had released a weapon into the wild, then acted surprised when people used it.

The economic model is equally cynical. Sora videos cost OpenAI about $5 in computing power each to produce, while users pay $20 monthly for the privilege of generating 100 videos every 24 hours. It's a business model predicated on the mass production of synthetic media, monetizing the erosion of shared reality one deepfake at a time.

The Credibility Crisis

Altman's claims about imminent superintelligence have become increasingly difficult to take seriously. In January 2025, he published a blog post declaring "we are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it". By his accounting, we're mere months away from AI agents that can "join the workforce and materially change the output of companies". Superintelligence, he suggested, could arrive during Trump's term.

The problem is that OpenAI's own recent releases tell a different story. GPT-5, launched to much fanfare, disappointed power users who found it barely distinguishable from GPT-4. The much-hyped improvements turned out to be mostly infrastructure changes—a router system designed not to unlock superhuman intelligence but to monetize OpenAI's 700 million weekly free users through better ad targeting and e-commerce integration. The "unified system" is less a breakthrough in AI capability than a breakthrough in extracting revenue from attention.

Meanwhile, Chinese competitor DeepSeek has been eating OpenAI's lunch, releasing models that match or exceed OpenAI's performance at a fraction of the development cost. The disruption forced OpenAI to slash prices and scramble to differentiate itself, revealing just how commoditized the underlying technology has become. When your competitive moat evaporates in months, claims of imminent superintelligence start to sound less like prophecy and more like marketing.

Even OpenAI's closest observers are skeptical. "OpenAI is in a very bad position," wrote one analyst on Reddit's rationalist community, "and Altman's claims about imminent superintelligence are hype to keep recruits and investors interested". The company is hemorrhaging key personnel—nearly all its lead scientists have departed—which is "uncommon for individuals to depart from a company poised to achieve AGI". The people who would know best whether superintelligence is near are voting with their feet.

The Inequality Engine

But the most profound shift isn't technical—it's economic. OpenAI is no longer positioning itself as humanity's shepherd into a post-scarcity future. It's becoming an inequality engine, a mechanism for concentrating unprecedented wealth and power in the hands of a tiny elite while displacing the workers whose labor built the economy it's now automating away.

The numbers are staggering. OpenAI went from a $29 billion valuation in 2023 to $500 billion by October 2025—larger than SpaceX, making it the world's most valuable private company. This wealth creation is happening at machine speed, minting billionaires faster than any previous technological revolution. The AI boom has created 498 "unicorn" companies valued at over $1 billion, with a combined worth of $2.7 trillion. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman stands to receive equity in the restructured for-profit entity potentially valued at $150 billion.

Meanwhile, the workers who train these models earn less than $2 per hour in countries like Kenya. The disparity is obscene: Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang made $50 million in 2023 while the human trainers making his AI "learn" scraped by on poverty wages. This is the "shared prosperity" Altman promised—prosperity for shareholders, precarity for everyone else.

Goldman Sachs estimates that AI could displace 6-7% of U.S. workers, potentially affecting 300 million jobs globally. OpenAI's own exposure data suggests that more than 30% of workers could see at least half their job tasks disrupted by generative AI. The sectors most at risk aren't blue-collar manufacturing—the jobs already hollowed out by previous waves of automation—but white-collar knowledge work: legal analysis, software development, customer service, financial services. Women are particularly vulnerable, facing 36% exposure compared to 25% for men, due to their overrepresentation in administrative and clerical roles.

The early warning signs are already visible. Employment in tech-exposed occupations is falling below pre-pandemic trends, with unemployment among young tech workers rising nearly 3 percentage points since early 2025. Marketing consulting, graphic design, office administration, and call centers are all seeing below-trend job growth amid reports of AI-driven efficiency gains. A recent MIT study found that 95% of generative AI pilot business projects are failing, but that hasn't stopped companies from using AI as justification for mass layoffs.

What makes this particularly galling is that Altman himself acknowledges the problem while doing nothing to address it. In a February 2025 essay, he admitted that "the balance of power between capital and labor could easily get messed up". His proposed solution? A "compute budget"—some vague notion of rationing AI access—as if the problem of concentrated wealth could be solved by better resource allocation rather than structural change. It's the kind of technocratic non-answer that sounds profound in a Medium post but means nothing in practice.

The Class Analysis

The piece so far has examined OpenAI's trajectory from intellectual and moral perspectives, but it needs a class analysis too. Sora 2 represents not just a technological milestone but a class weapon—a tool that consolidates power in the hands of capital while further disempowering labor. To understand who truly benefits from this technology and who bears its costs, we must examine the material relations of production that underpin it.

Who benefits from Sora 2? The answer is straightforward: investors, executives, and already-privileged creators who can leverage the technology to enhance their market position. OpenAI's valuation skyrocketed from $29 billion in 2023 to $500 billion by October 2025, making it the world's most valuable private company. This wealth creation happened at machine speed, minting billionaires faster than any previous technological revolution.

Sam Altman, despite technically holding no equity in OpenAI, stands to receive shares potentially valued at $150 billion if the company completes its transition to a for-profit entity. His personal net worth of $1.2 billion comes from investments in tech companies like Reddit, Stripe, and Airbnb—positions that give him a stake in the broader AI ecosystem that benefits from technologies like Sora 2.

The venture capital firms backing OpenAI—including Microsoft with its $13.75 billion investment—are positioned to capture enormous returns. Microsoft negotiated a particularly clever arrangement: while it loses access to OpenAI's models once "AGI is achieved," AGI is defined not as human-level intelligence but as a system capable of generating $100 billion in profits. The declaration of "sufficient AGI" remains at OpenAI's "reasonable discretion," meaning the goalposts can be perpetually moved to keep profits flowing.

Beyond OpenAI's direct investors, Sora 2 benefits a class of already-privileged creators and media professionals who can use the technology to reduce production costs while maintaining their market position. A Hollywood studio can replace background actors with AI-generated figures. A marketing agency can produce commercials without hiring crews. A news organization can create video content without journalists. In each case, capital owners and managers benefit while workers are displaced.

Who gets harmed by Sora 2? The list is long and growing, encompassing both direct job displacement and more subtle forms of economic harm. The most immediately affected are video production professionals: cinematographers, editors, visual effects artists, animators, and production crews. These skilled workers, who have spent years developing their craft, now face competition from a $20/month subscription service.

But the harm extends beyond direct displacement. Sora 2 accelerates the "barbell economy" phenomenon—growth at the high and low ends of the wage spectrum but fewer opportunities in the middle. As Goldman Sachs research indicates, AI "could affect 40% of jobs and widen inequality between nations" because "the benefits of AI-driven automation often favour capital over labour."

The displacement is already visible. Employment in tech-exposed occupations is falling below pre-pandemic trends, with unemployment among young tech workers rising nearly 3 percentage points since early 2025. Marketing consulting, graphic design, office administration, and call centers are all seeing below-trend job growth amid reports of AI-driven efficiency gains.

Women are particularly vulnerable, facing 36% exposure compared to 25% for men, due to their overrepresentation in administrative and clerical roles that AI can automate. This gendered impact reflects how technological change often exacerbates existing inequalities rather than alleviating them.

Beyond direct job displacement, Sora 2 imposes significant environmental and human costs that disproportionately affect marginalized communities. The environmental impact is staggering—AI already accounts for about 20% of global data-center power consumption, and video generation with Sora requires nearly 1 kWh to generate just 5 seconds of video. This massive energy consumption contributes to climate change, which disproportionately harms low-income communities and communities of color.

The human cost of training AI models falls on workers in the Global South. Kenyan workers helping to refine ChatGPT's algorithms earned less than $2 per hour while being exposed to harmful and explicit content. These "digital sweatshops" represent the hidden foundation of AI's supposed magic—exploited labor making the technology appear seamless and automatic to users in wealthy countries.

This pattern of exploitation is not accidental but structural. AI development relies on a global division of labor where well-paid engineers in Silicon Valley design systems while low-paid workers in the Global South perform the tedious, often psychologically damaging work of data labeling and content moderation. The profits flow to capital owners in developed countries while the costs are externalized to vulnerable workers elsewhere.

A working-class perspective on Sora 2 would reject the technological determinism that dominates mainstream discourse—the idea that technological development is neutral and inevitable. Instead, it would recognize that technologies are developed within specific social relations and serve particular class interests. From this perspective, Sora 2 is not just a tool but a weapon in the class struggle—a means of increasing capital's power over labor.

The relevant questions are not "Can we create realistic video from text?" but "Who controls this technology?" and "Who benefits from its deployment?" A working-class analysis would demand democratic control of AI, a just transition for displaced workers, fair distribution of gains, and global justice for those exploited in AI's supply chain.

The tragedy of Sora 2 is not that it exists but that it serves the wrong master. The same technology that creates deepfakes for social media could be used for education, healthcare, climate modeling, or other socially valuable purposes. The problem is not the technology itself but the social relations that shape its development and deployment.

An alternative approach would treat AI as a public good rather than a private commodity. It would be developed through democratic institutions with worker and community representation. Its deployment would be guided by social need rather than profit potential. Its benefits would be shared broadly rather than concentrated in the hands of a few.

This alternative is not utopian but practical. The resources and knowledge to develop AI exist—they simply need to be organized differently. The question is not whether we can build systems like Sora 2 but who they should serve and how their benefits should be distributed.

The Nonprofit Illusion

OpenAI's transformation from nonprofit research lab to profit-maximizing corporation is the original sin from which all these other betrayals flow. Founded in 2015 with $1 billion in pledges from Elon Musk and others, OpenAI positioned itself as the virtuous alternative to corporate AI labs, promising to develop artificial general intelligence for the benefit of all humanity.

That mission lasted approximately four years. In 2019, OpenAI created a "capped-profit" subsidiary that could raise money from investors while theoretically remaining under nonprofit control. The cap was set generously—investors could earn up to 100 times their investment before hitting the limit. By 2024, that arrangement was deemed insufficiently lucrative, and OpenAI announced plans to fully convert to for-profit status.

The plan faced immediate pushback. Attorneys general in California and Delaware raised concerns about a nonprofit worth billions converting its assets into private profit. Nobel laureates and AI insiders signed protest letters. Elon Musk, who helped found the organization, sued, alleging that Altman and his allies had "systematically drained the nonprofit of its valuable technology and personnel" to enrich themselves. OpenAI eventually backed down, announcing in May 2025 that it would restructure as a public benefit corporation rather than a pure for-profit entity. But the damage was done—the company's credibility as a mission-driven organization was shattered.

The uncomfortable truth is that OpenAI set a dangerous precedent. "Why would any entrepreneur or investor choose to establish a start-up and pay taxes and give up equity when they could simply form a nonprofit, collect 'donations,' and convert it into a corporation later to pursue profits?" asked one observer. No government should enable such a loophole, yet OpenAI has spent years exploiting exactly that structure.

Microsoft, which has invested $13.75 billion in OpenAI, negotiated a particularly clever arrangement: the company loses access to OpenAI's models once AGI is achieved. But AGI is defined financially—not as a system that surpasses human intelligence, but as one capable of generating $100 billion in profits. The declaration of "sufficient AGI" remains at the "reasonable discretion" of OpenAI's board, meaning the company can perpetually move the goalposts to keep the money flowing.

The Slop Future

OpenAI's recent product launches suggest the company has given up even pretending to work toward beneficial AGI. Beyond Sora 2's deepfake factory, the company announced in October that it would allow "erotica for verified adults" on ChatGPT. Altman defended the decision by declaring OpenAI "not the elected moral police of the world"—a remarkable statement from someone who just months earlier was claiming his company held "enormous responsibility on behalf of all of humanity".

The shift is stark. OpenAI is no longer in the business of curing cancer or solving high-energy physics, aspirations Altman invoked when describing AI's potential. It's in the business of generating slop—low-effort, high-volume synthetic content designed to capture attention and extract revenue. It's algorithmic fast food, empty calories for an information economy already suffering from malnutrition.

This is what "democratizing AI" looks like in practice: not tools that empower workers or solve pressing social problems, but tech that makes it easier to flood the internet with garbage, to create fake news, to automate away knowledge work, to generate pornography on demand. The "Cambrian explosion" of creativity Altman promised looks a lot like a race to the bottom.

The AI slop is already having measurable negative effects. A Stanford study found that 40% of workers received AI slop at work in the previous month, taking an average of two hours to fix each instance. Workers report they "no longer trust their AI-enabled peers, find them less creative, and find them less intelligent or capable". The technology that was supposed to augment human intelligence is instead degrading trust and productivity.

The Billionaire's Burden

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of OpenAI's trajectory is how closely it tracks the incentives of its investors. The company is hemorrhaging cash—$5.3 billion in losses on $3.5 billion in revenue in 2024, with operating losses of $7.8 billion in the first half of 2025 alone. OpenAI projects $115 billion in cumulative losses by 2029. These are not the financials of a company confident in its path to superintelligence. They're the financials of a company desperately pivoting toward any business model that might stem the bleeding.

Hence the ads. Hence the e-commerce partnerships. Hence Sora 2's transformation into a social media platform where OpenAI can harvest attention and monetize virality. The company is pursuing what one analysis called "five paths to monetization"—API access, subscriptions, an app store of custom GPTs, direct-to-consumer products, and eventually advertising at scale. None of these paths lead to AGI. They lead to quarterly earnings.

The AI wealth boom is creating fortunes at unprecedented speed, but the spoils are flowing almost entirely to a tiny elite. The combined net worth of the top five tech billionaires increased 250% between 2010 and 2021, while median household wealth grew just 10%. AI unicorns achieve billion-dollar valuations with half the employees of traditional unicorns, demonstrating 50% greater "workforce efficiency"—which is to say, they generate massive wealth while employing far fewer people.

This is the future OpenAI is building: one where a handful of companies control increasingly powerful AI systems, where the benefits of automation accrue to capital rather than labor, where the productivity gains that could reduce working hours and improve quality of life instead concentrate wealth and eliminate jobs. It's a vision of shared prosperity only if you define "shared" as "captured by shareholders."

The Reckoning

The tragedy of OpenAI isn't just that it abandoned its principles for profit. It's that the principles themselves were always somewhat illusory—a marketing story designed to differentiate the company from its corporate competitors while it built the same extractive systems they were building. The rhetoric of "ensuring AGI benefits all of humanity" was always going to collide with the material reality of operating under capitalism, where companies optimize for shareholder value and externalize harm.

But there was a moment, however brief, when it seemed like OpenAI might thread that needle—that it might use its nonprofit structure and technical leadership to push the field toward genuinely beneficial outcomes. That moment is gone. What we have instead is a company whose CEO blogs about the coming "Gentle Singularity" while shipping products that make reality itself suspect, whose safety researchers quit in frustration while leadership chases ad revenue, whose astronomical valuation is built on automating away millions of jobs while creating wealth for a tiny elite.

Altman's latest gambit is telling: last month he announced that OpenAI would introduce revenue-sharing for copyright holders whose characters get generated in Sora. It's the company's answer to the intellectual property theft baked into its business model—not "stop stealing," but "we'll cut you in if you let us." It's the AI equivalent of a protection racket, and it reveals the transactional logic at the heart of OpenAI's current incarnation. Everything is for sale. Everyone has a price.

The bitter irony is that Altman might be right about one thing: we are approaching a threshold. Not the threshold to superintelligence—the actual evidence for that remains stubbornly absent despite years of scaling models and burning billions in compute. Rather, we're approaching the threshold where AI's harms become too large to ignore, where the inequality it generates becomes socially destabilizing, where the slop it produces makes shared reality impossible.

If that is the future OpenAI is building, then perhaps the company should drop the pretense. Stop talking about AGI and superintelligence and humanity's flourishing. Admit you're a profit-maximizing corporation like any other, that your mission is shareholder value, that the grand pronouncements about existential risk and beneficial AI were always just marketing. At least then we'd know who we're dealing with.

But honesty has never been Silicon Valley's strong suit. So instead we get more blog posts about singularities, more promises of abundance just around the corner, more products that make the world measurably worse while generating immense wealth for a tiny few. We get Sora 2 and its flood of deepfakes, ChatGPT with ads, AI systems that displace workers while enriching executives. We get, in other words, exactly what we should have expected: the billionaire's burden of responsibility transmuted into the billionaire's windfall of profit.

The Prometheus of Greek mythology stole fire from the gods to give to humanity and was punished with eternal torment. OpenAI's version of Prometheus has learned a more valuable lesson: why give away fire when you can monetize it?